1. "Such Trivia As Comic Books"

Introducing the Subject

"And I verily do suppose that in the braines and hertes of children, which be membres spirituall, whiles

they be tender, and the little slippes of reason begynne in them to bud, ther may happe by evil custome

some pestiferous dewe of vice to perse the sayde membres, and infecte and corrupt the soft and tender

buddes."

- Sir Thomas Eliot (1531)

Gardening consists largely in protecting plants from blight and weeds, and the same is true of attending to

the growth of children. If a plant fails to grow properly because attacked by a pest, only a poor gardener

would look for the cause in that plant alone. The good gardener will think immediately in terms of general

precaution and spray the whole field. But with children we act like the bad gardener. We often fail to carry

out elementary preventive measures, and we look for the causes in the individual child. A whole highsounding

terminology has been put to use for that purpose, bristling with "deep emotional disorders," "profound psychogenic features" and "hidden motives baffling in their complexity." And children are

arbitrarily classified - usually after the event - as "abnormal," "unstable" or "predisposed," words that often fit their environment better than they fit the children. The question is, Can we help the plant without attending to the garden?

A number of years ago an attorney from a large industrial city came to consult me about an unusual problem. A group of prominent businessmen had become interested in a reformatory for boys. This attorney knew of my work in mental hygiene clinics and wanted me to look over this reformatory and advise whether, and how, a mental hygiene department could be set up there. "Very good work is done there," he told me. "It is a model place and the boys are very contented and happy. I would like you to visit the institution and tell us whether you think we need a mental hygiene clinic there."

I spent some time at that reformatory. It was a well laid out place with cottages widely spaced in a beautiful landscape. I looked over the records and charts and then suggested that I wanted to see some individual children, either entirely alone or with just the attorney present. There was considerable difficulty about this. I was told that it would be much better if the director or some of his assistants would show me around and be present during any interviews. Eventually, however, I succeeded in going from cottage to cottage and seeing some boys alone. I told them frankly who I was and finally asked each child,"Supposing I could give you what you want most, what would you choose?" There was only one answer:"I want to go home."

The children's logic was simple and realistic. The adults said this was not a jail because it was so beautiful. But the children knew that the doors were locked - so it was a jail. The lawyer (who heard some of this himself) was crestfallen. He had never spoken to any of the inmates alone before. "What a story!" he said."They all want to get out!" I remember contradicting him. The real story is not that they want to get out, I said. The story is how they got in. To send a child to a reformatory is a serious step. But many children's court judges do it with a light heart and a heavy calendar. To understand a delinquent child one has to know the social soil in which he developed and became delinquent or troubled. And, equally important, one should know the child's inner life history, the way in which his experiences are reflected in his wishes, fantasies and rationalizations. Children like to be at home, even if we think the home is not good. To replace a home one needs more than a landscape gardener and a psychiatrist. In no inmate in that reformatory, as far as I could determine, had there been enough diagnostic study or constructive help before the child was deprived of his liberty.

The term mental hygiene has been put to such stereotyped use, even though embellished by psychological

profundities, that it has become almost a cliché. It is apt to be forgotten that its essential meaning has to do

with prevention. The concept of juvenile delinquency has fared similarly since the Colorado Juvenile

Court law of half a century ago: "The delinquent child shall be treated not as a criminal, but as misdirected

and misguided, and needing aid, encouragement, help and assistance." This was a far-reaching and

history-making attitude, but the great promise of the juvenile-court laws has not been fulfilled. And the

early laws do not even mention the serious acts which bring children routinely to court nowadays and

which juvenile courts now have to contend with. The Colorado law mentions only the delinquent who"habitually wanders around any railroad yards or tracks, or jumps or hooks to any moving train, or enters

any car or engine without lawful authority."

Streetcar hoppings like streetcars themselves, have gone out of fashion. In recent years children's-court judges have been faced with such offenses as assault, murder, rape, torture, forgery, etc. So it has come about that at the very time when it is asked that more youthful offenders be sent to juvenile courts, these courts are ill prepared to deal with the types of delinquency that come before them. Comic books point that out even to children. One of them shows a pretty young girl who has herself picked up by men in cars and then robs them, after threatening them with a gun. She calls herself a "hellcat" and the men "suckers." Finally she shoots and kills a man. When brought before the judge she says defiantly: "You can't pin a murder rap on me! I'm only seventeen! That lets me out in this state!"

To which the judge replies: "True - but I can hold you for juvenile delinquency!"

Some time ago a judge found himself confronted with twelve youths, the catch of some hundred and fifty

policemen assigned to prevent a street battle of juvenile gangs. This outbreak was a sequel to the killing of

a fifteen-year-old boy who had been stabbed to death as he sat with his girl in a parked car. The twelve

boys were charged with being involved in the shooting of three boys with a .22-caliber zip gun and a .32

revolver. The indignant judge addressed them angrily, "We're not treating you like kids any longer. . . . If

you act like hoodlums you'll be treated like hoodlums." But were these youths treated like I 'kids" in the

first place? Were they protected against the corrupting influence of comic

books which glamorize and advertise dangerous knives and the guns that can be converted into 'deadly weapons?

The public is apt to be swayed by theories according to which juvenile delinquency is treated as an entirely individual emotional problem, to be handled by individualistic means. This is exemplified by the very definition of juvenile delinquency in a recent psychopathological book on the subject:

"We have assigned the generic term of delinquency to all these thoughts,

actions, desires and strivings which deviate from moral and ethical

principles." Such a definition diffuses the concept to such an extent that no concrete meaning remains. This unsocial way of thinking is unscientific and leads to confused theory

and inexpedient practice. For example, one writer stated recently that "too much exposure to horror stories

and to violence can be a contributing factor to a child's insecurity or  fearfulness," but it could not "make a

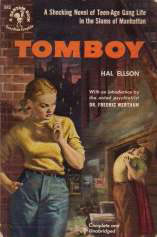

child of any age a delinquent." Can such a rigid line be drawn between the two? As Hal Ellson has shown

fearfulness," but it could not "make a

child of any age a delinquent." Can such a rigid line be drawn between the two? As Hal Ellson has shown

again recently in his book Tomboy, children who commit serious delinquencies often suffer from

"insecurity and fearfulness." And children who are insecure and fearful are certainly in danger of

committing a delinquent act. Just as there is such a thing as being predelinquent, so there are conditions

where a child is pre-insecure, or prefearful. Would it not be better, for purposes of prevention, instead of

making an illogical contrast between a social category like delinquency and a psychological category like

fearfulness, to think of children in trouble - in trouble with society, in trouble with their families or in

trouble with themselves? And is it not likely that "too much exposure to horror stories and to violence" is

bad for all of them when they get into trouble, and before they get into trouble?

In the beginning of July, 1950, a middle-aged man was sitting near the bleachers at the Polo Grounds watching a baseball game. He had invited the thirteen-year-old son of a friend, who sat with him excited and radiating enthusiasm.

Suddenly the people sitting near by heard a sharp sound. The middle-aged man, scorecard in hand, slumped over and his young friend turned and was startled to see him looking like a typical comic-book illustration. Blood was pouring from his head and ears. He died soon afterwards and was carried away. Spectators rushed to get to the vacant seats, not realizing at all what had happened.

In such a spectator case the police go in for what the headlines like to call a dragnet. This had to be a pretty big one. In the crowded section of the city overlooking the Polo Grounds there were hundreds of apartment buildings in a neighborhood of more than thirty blocks, and from the roof of any of them someone could have fired such a shot. As a matter of fact, at the very beginning of the search detectives confiscated six rifles from different persons. Newspapers and magazines played up the case as "Mystery Death," the "Ball Park Death" and "The Random Bullet."

Soon the headlines changed to "Hold Negro Youth in Shooting" and the stories told of the "gun-happy

fourteen-year-old Negro boy" who was being held the authorities. Editorials reproached his aunt for being"irresponsible" in the care and training of the youngster" and for "being on the delinquent side of the adult

ledger."

In the apartment where this boy Willie lived with his great-aunt, and on the roof of the building, the police found "two .22-caliber rifles, a high-powered .22-caliber target pistol, ammunition for all three guns, and a quantity of ammunition for a Luger pistol."

This served as sufficient reason to arrest and hold the boy's great-aunt on a Sullivan Law charge (for possession of a gun). She was not released until the boy, who was held in custody all during this time, had signed a confession stating that he had owned and fired a .45-caliber pistol - which, incidentally, was never found.

In court the judge stated, "We cannot find you quilty, but I believe you to be guilty." With this statement he sentenced Willie to an indeterminate sentence in the state reformatory.

For the public the case was closed. The authorities had looked for the cause of

this extraordinary event, which might have affected anyone in the crowd, in one

little boy and took it out on him, along with a public slap at his aunt. They

ignored the fact that other random shootings by juveniles had been going on in

this as in other sections of the city.  Only a few days after the Polo Grounds

shooting, a passenger on a Third Avenue train was wounded by a shot that came

through the window. But with Willie under lock and key, the community

thought that its conscience was clear.

Only a few days after the Polo Grounds

shooting, a passenger on a Third Avenue train was wounded by a shot that came

through the window. But with Willie under lock and key, the community

thought that its conscience was clear.

It happened that I had known Willie for some time before this shooting incident

at the stadium. He had been referred to the Lafargue Clinic - a free psychiatric

clinic in Harlem - by the Reverend Shelton Hale Bishop as a school problem. He

was treated at the Clinic. We had studied his earliest development. We knew when he sat up, when he got

his first tooth, when he began to talk and walk, how long he was bottle fed, when he was toilet trained. Psychiatrists and social workers had conferences about him.

Wille had been taken care of by his great-aunt since he was nineteen months old. His parents had separated shortly before. This aunt, an intelligent, warm, hard-working woman, had done all she could to give Willie a good upbringing. She worked long hours at domestic work and with her savings sent him (at the age of two) to a private nursery school, where he stayed until he was eight. Then she became ill, could not work so hard and so could not afford his tuition there. He was transferred to a public school where he did not do so well, missing attention he had recieved at the private school.

At that time his aunt took him to the Lafargue Clinic. He had difficulty with his eyes and had to wear glasses which needed changing. According to his aunt he had occassionally suffered from sleepwalking which started when he was six or seven. Once when his great-aunt waked him up from such a somnambulistic state he said, half-awake, that he was "going to look for his mother." He was most affectionate with his aunt and she had the same affection for him. She helped him to get afternoon jobs at the neighborhood grocery stores, delivering packages.

Willie was always a rabid comic-book reader. He "doted" on them. Seeing all

their pictures of brutality and shooting and their endless glamorous

advertisements of guns and knives, his aunt had become alarmed - years before

the shooting incident - and did not permit him to bring them into the house. She

also forbade him to read them. But of course such direct action on the part of the parent has no chance of succeeding in an environment where comic books are all over the place in enormous quantities. She encountered a further obstacle, too.

Workers at a public child-guidance agency connected with the schools made her

distrust her natural good sense and told her she should let Willie read all the

comic books he wanted. She told one of the Lafargue social workers, "I didn't

like for him to read these comic books, but I figured they knew better than I did." The Lafargue Clinic has some of these comic books. They are before me as I am writing this, smudgily printed and well thumbed, just as he used to pour over them with his weak eyes. Here is the lecherous-looking bandit overpowering the attractive girl who is dressed (if that is the word) for very hot weather ("She could come in handy, then! Pretty little spitfire, eh!") in the typical pre-rape position. Later he threatens to kill her:

"Yeah, it's us, you monkeys, and we got an old friend of yours here... Now unless you want to see somp'n FATAL happen to here, u're gonna kiss that gold goodbye and lam out of here!"

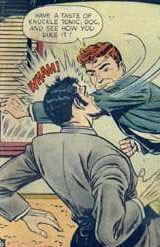

Here is violence galore, violence in the beginning, in the middle, at the end:

ZIP! CRASH! SOCK! SPLAT! BAM! SMASH!

(This is an actual sequence of six pictures illustrating brutal fighting, until in the seventh picture: "He's out

cold!")

Here, too, is the customary close-up of the surprised and frightened-looking policeman with his hands half-raised saying:

NO - NO! DON'T SHOOT

as he is threatened by a huge fist holding a gun to his face! This is followed by mild disapproval ("You've

gone too far! This is murder!") as the uniformed man lies dead on the ground. This comic book is endorsed by child specialists who are connected with important institutions. No wonder Willie's aunt did

not trust her own judgment sufficiently.

The stories have a lot of crime and gunplay and, in addition, alluring advertisements of guns, some of them full-page and in bright colors, with four guns of various sizes and descriptions on a page:

Get a sweet-shootin' [mfg's name] gun and get in on the fun!

Here is the repetition of violence and sexiness which no Freud, Krafft-Ebing or Havelock Ellis ever

dreamed could be offered to children, and in such profusion. Here is one man mugging another, and graphic pictures of the white man shooting colored natives as though they were animals: "You sure must

have treated these beggars rough in that last trip though here!" And so on. This is the sort of thing that

Willie's aunt wanted to keep him from reading.

When the Lafargue staff conferred about this case, as we had about so many others, we asked ourselves: How does one treat such a boy? How does one help him to emotional balance while emotional excitement is instilled in him in an unceasing stream by these comic books? Can one be satisfied with the explanation that he comes from a broken family in an underprivileged neighborhood? Can one scientifically disregard what occupied this boy's mind for hours every day?

Can we say that this kind of literary and pictorial influence had no effect at all, disregarding our clinical experience in many similar cases? Or can we get anywhere by saying that he must have been disordered in the first place or he would not have been fascinated by comic books?

That would have meant ignoring the countless other children equally fascinated whom we had seen. Evidently in Willie's case there is a constellation of many factors. Which was finally the operative one? What in the last analysis tipped the scales?

Slowly, and at first reluctantly, I have come to the conclusion that this chronic stimulation, temptation and

seduction by comic books, both their content and their alluring advertisements of knives and guns, are

contributing fac tors to many children's maladjustment.

tors to many children's maladjustment.

All comic books with their words and expletives in balloons are bad for reading, but not every comic book is bad for children's minds and emotions. The trouble is that the"good" comic books are snowed under by those which glorify violence, crime and sadism.

At no time, up to the present time, has a single child ever told me as an excuse for delinquency or for misbehavior that comic books were to blame. Nor do I nor my associates ever question a child in such a way as to suggest that to him. If I find a child with a fever I do not ask him, "What is the cause of your fever? Do you have measles?" I examine him and make my own diagnosis. It is our clinical judgment, in all kinds of behavior disorders and personality difficulties of children, that comic books do play a part. Of course they are not in the textbooks. But once alerted to the possibility, we unexpectedly found, in case after case, that comic books were a contributing factor not to be neglected.

I asked psychiatric colleagues, child psychologists and social workers. They knew nothing about comic

books. They knew there were such little books; they may even have had them in their waiting rooms. And

they knew about funny animal stories that children liked to read. Comic books, they assumed, were just reprints of comic strips from newspapers or Sunday supplements - "like 'Bringing Up Father,' you know" -

or other such humorous sequences. Why, they felt, should any physician take a serious interest in them?

No one had any idea of the enormous number of such books. The industry had not given out any figures,

nor had a magazine or newspaper published any. When I made public the result of my own estimates and

computations, namely that there were (then) some sixty million comic books a month, my statement was

met with absolute incredulity. Some people thought that it was a misprint, and that sixty million must be

the yearly figure. But shortly afterwards authoratative magazines and newspapers (such as Business Week)

repeated my figure as an accurate one.

Nor was I believed at first when I stated that children spend an inordinate amount of time with comic

books, many of them two or three hours a day. I asked those working with groups of children, "How can

you get the 'total picture' of a child you leave out entirely what occupies him two or three hours a day?"

Again and again it happened that when they made inquiries they told me of finding out to their surprise

how many comic books children read, how bad these books are and what an enormous amount of time

children spend with them.

Some time after I had become aware of the effects of comic books, a woman visited me. She was a civic

leader in the community and invited me to give some lectures on child guidance, education and

delinquency. We had a very pleasant conversation. It happened that on that very morning I had been

overruled by the Children's Court. I had examined a boy who had threatened a woman teacher with a

switchblade knife. Ten years before, that would have been a most unusual case, but now I had seen quite a

number of similar ones. This particular boy seemed to me a very good subject for treatment. He was not

really a "bad boy," and I do not believe in the philosophy that children have instinctive urges to commit

such acts.

In going over his life, I had asked him about his reading. He was enthusiatic about comic books. I looked

over some of those he liked best. They were filled with alluring tales a shooting, knifing, hitting and

strangling. He was so intelligent, frank and open that I considered him not an inferior child, but a superior one.

I know that many people glibly call such a child maladjusted; but in reality he was a child well adjusted to

what we had offered him to adjust to. In other words, I felt this was a seduced child. But the court decided

otherwise. They felt that society had to be protected from this menace. So they sent him to a reformatory.

In outlining to the civic leader what I would talk about, I mentioned comic books. The expression of her

face was most disappointed. Here she thought she had come to a real psychiatrist. She liked all the other

subjects I had mentioned; but about comic books she knew everything herself.

"I have a daughter of eleven," she said. "She reads comic books. Of course only the animal comics. I have

heard that there are others, but I have never seen them. Of course I would never let them come into my

home and she would never read them. As for what you said about crime comics, Doctor, they are only

read by adults. Even so, these crime comics probably aren't any worse than what children have read all

along. You know, dime novels and all that." She looked at me then with a satisfied look, pleased that there

was one subject she could really enlighten me about.

I asked her, "In the group that I am to speak to, do you think some of the children of these women have

gotten into trouble with stealing or any other delinquency?"

She bent forward confidentially. "You've guessed it," she said. "That's really why we want these lectures.

You'd be astonished at what these children from these good middle-class homes do nowadays. You know,

you won't believe it, but they break into apartments, and a group of young boys molested several small

girls in our neighborhood! Not to speak of the mugging that goes on after dark."

"What happens to these boys?" I asked her.

"You know how it is," she said. "One has to hush these things up as much as possible, but when it got too

bad, of course, they were put away."

After this conversation, I felt that not only did I have to be a kind of detective to

trace some of the roots of the modern mass delinquency, but that I ought to be

some kind of defense counsel for the children who were condemned and

punished by the very adults who permitted them to be tempted and seduced.

As  far as children are concerned, the punishment does not fit the crime. I have

noticed that a thousand times. Not only is it cruel to take a child away from his

family, but what goes on in reformatories hurts children and does them lasting

harm. Cruelty to children is not only what a drunken father does to his son, but

what those in high estate, in courts and welfare agencies, do to straying youth.

far as children are concerned, the punishment does not fit the crime. I have

noticed that a thousand times. Not only is it cruel to take a child away from his

family, but what goes on in reformatories hurts children and does them lasting

harm. Cruelty to children is not only what a drunken father does to his son, but

what those in high estate, in courts and welfare agencies, do to straying youth.

This civic leader was only one of many who had given me a good idea of what I

was up against, but I took courage from the fact that societies for the prevention

of cruelty to children were formed many years after societies for the prevention

of cruelty to animals.

I began to study the effects of comic-book reading more consistently and systematically. We saw many

kinds of children: normal ones; troubled ones; delinquents; those from well-to-do families and from the

lowest rung of the economic ladder; children from different parts of the city; children referred by different

public and private agencies; the physically well and the physically ill and handicapped; children with

normal, subnormal and superior intelligence.

Our research involved not only the examination, treatment and follow-up study of children, but also discussions with parents, relatives, social workers, psychologists, probation officers, writers of children's books, camp counsellors, physicians - especially pediatricians - and clergymen. We made the interesting observation that those nearest to actual work with children regarded comic books as a powerful influence, disapproved of them and considered them harmful. On the other hand, those with the most highly specialized professional training knew little or nothing about comic books and assumed them to be insignficant.

Our study concerned itself with comic books and not with newspaper comic strips. There are fundamental differences between the two, which the comic-book industry does its best to becloud. Comic strips appear mainly in newspapers and Sunday supplements of newspapers. Comic books are separate entities, always with colored pictures and a glaring cover. They are called "books" by children, "pamphlets" by the printing trade and "magazines" by the Post Office which accords them second class mailing privileges.

Comic books are most widely read by children, comic strips by adults. There is, of course, an overlap, but the distinction is a valid and important one. Newspaper comic strips function under a severe censorship exercised by some 1,500 newspaper editors of the country who sometimes reject details or even whole sequences of comic strips. For comic books there exists no such censorship by an outside agency which has the authority to reject. When comic strips are reprinted as comic books, the censorship that existed before, when they were intended for adults, disappears and the publisher enjoys complete license. He can (and sometimes does) add a semipornographic story for the children, for example, and a gory cover - things from which censorship protects the adult comic strip reader.

Some of my psychiatric friends regarded my comics research as a Don Quixotic enterprise. But I gradually learned that the number of comic books is so enormous that the pulp paper industry is vitally interested in their mass production. If anything, I was fighting not windmills, but paper mills. Moreover, a most important part of our research consisted in the reading and analysis of hundreds of comic books. This task was not Quixotic but Herculean - reminiscent, in fact, of the job of trying to clean up the Augean stables.

As our work went on we established the basic ingredients of the most numerous and widely read comic books: violence; sadism and cruelty; the superman philosophy,

an offshoot of Nietzsche's superman who said, "When you go to women, don't forget the whip."

[fn. Friedrich Nietzsche was a German philosopher of the late 19th century who challenged the foundations of traditional morality and Christianity. He believed in life, creativity, health, and the realities of the world we live in, rather than those situated in a world beyond. Central to Nietzsche's philosophy is the idea of "life-affirmation," which involves an honest questioning of all doctrines which drain life's energies, however socially prevalent those views might be. Often referred to as one of the first "existentialist" philosophers, Nietzsche has inspired leading figures in all walks of cultural life, including dancers, poets, novelists, painters, psychologists, philosophers, sociologists and social revolutionaries. ]

We also found that what seemed at first a problem in child psychology had much wider implications. Why does our civilization give to the child not its best but its worst, in paper, in language, in art, in ideas? What is the social meaning of these supermen, superwomen, super-lovers, super boys, supergirls, super-ducks, super-mice, super-magicians, super-safecrackers?

How did Nietzsche get into the nursery?

The opposition took various forms. I was called a Billy Sunday.

[fn. (William Ashley Sunday), 1863-1935, American evangelist, b. Ames, Iowa, in the era around World War I. A professional

baseball player (1883-90), he later worked for the Young Men's Christian Association in Chicago (1891-95) and, during that

time, became associated with the Presbyterian itinerant evangelist J. Wilbur Chapman (1859-1918).]

Later that was changed to Savonarola.

[fn. Savonarola, 1452-98, Italian religious reformer, b. Ferrara. He joined (1475) the Dominicans. In 1481 he went to San

Marco, the Dominican house at Florence, where he became popular for his eloquent sermons, in which he attacked the vice and

worldliness of the city, as well as for his predictions (several of which, including the death date of Innocent VIII, turned out to

be true).]

Millions of comic books in the hands of children had whole pages defending comic books against "one Dr. Wertham." A comic strip sequence syndicated in newspapers was devoted to a story of the famous child psychologist Dr. Fredrick Muttontop who speaks against crime comic books, but on returning to his old home town for a lecture on "Comic books, the menace to American childhood," is told that when he was a boy he used to read much worse things himself.

And the cover of a crime comic book showed a caricature of me as a psychiatrist tied to a chair in his office with mouth tightly closed and sealed with many strips of adhesive tape. This no doubt was wishful thinking on the part of the comic-book publishers.

But as our studies continued, it seemed to us that Virgilia Peterson, author and critic, stated the core of the question when she said:

The most controversial thing about Dr. Wertham's statements against comic books is the fact that anyone finds them controversial.

There were counterarguments and counteractions. These we took very seriously, read and followed carefully, and as a matter of fact incorporated into the social part of our research into the comic-book problem.

Little did I think when I started it that this study would continue for seven years. A specialist in child psychology referring to my correlation of crime comic books with violent forms of juvenile delinquency wrote disdainfully that no responsibility should be placed on "such trivia as comic books."

I thought that once, too. But the more children I studied, the more comic books I read, and the more I analyzed the arguments of comic book defenders, the more I learned that what may appear as "trivia" to adults are not trivia in the lives of many children.

An excerpt from Seduction of the Innocent by Fredric Wertham (Rinehart & Company, Inc. New York, Toronto 1953, 1954)